The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt: McKinley Mourns Death of VP & the Path to Mount Rushmore

Share

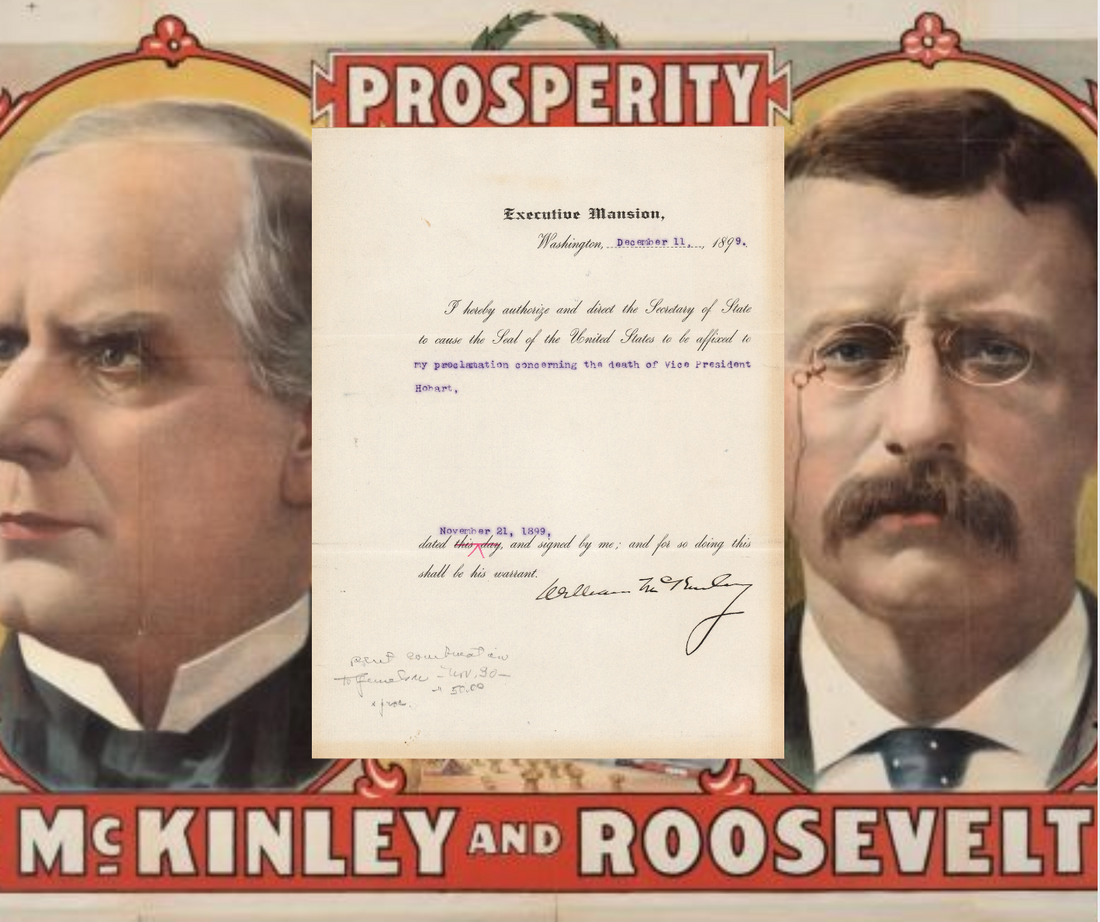

On December 11, 1899, President William McKinley sat in the Executive Mansion—what we now call the White House—and signed a single-page directive. The document, preserved on official letterhead, authorized the Secretary of State to affix the Seal of the United States to “my proclamation concerning the death of Vice President Hobart.”

With McKinley’s flowing signature at the bottom, the proclamation gave formal recognition to the loss of his vice president, Garret A. Hobart—a man not just vital to the administration, but deeply personal to McKinley himself.

The Illness and Death of Garret A. Hobart

Garret Augustus Hobart served as vice president from 1897 until his untimely death in 1899. Unlike many vice presidents of his era, Hobart was no mere figurehead. He was a skilled political operator and a trusted advisor, with a close friendship to McKinley that made him unusually influential for the office.

In the summer of 1899, Hobart’s health began to falter. Diagnosed with heart disease, he spent the summer resting in New Jersey and later joined McKinley and First Lady Ida McKinley at their Lake Champlain retreat. Despite this reprieve, Hobart’s condition worsened. On November 21, 1899, he passed away at age 55, leaving the vice presidency vacant and the administration without one of its key players.

This official document, issued twenty days later, marks the somber close to Hobart’s public service and life. Its existence reflects the formal grief of a government in mourning—and the beginning of a critical power vacuum in the executive branch.

The Vice Presidency Left Vacant: A Constitutional Gap

When Vice President Garret A. Hobart died on November 21, 1899, it exposed a critical flaw in the constitutional framework of the United States government: there was no formal process to fill a vacancy in the vice presidency. The Constitution, as originally written, provided for succession in the event of a president's death, but it offered no guidance on what to do if the vice president died or resigned. This silence left the office vacant until the next national election.

For more than a year, President William McKinley governed without a vice president—a notable absence in both political and practical terms. Hobart had not been a ceremonial figure; he was an active and influential member of the administration. He presided over the Senate, advised the president directly, and served as a political liaison between the White House and Congress. His death left a void not just in the line of succession but in the daily operations of the executive branch.

In an era before modern communications and formalized executive structures, the absence of a second-in-command with political capital and Senate authority presented real risks. Were McKinley to die or become incapacitated, the presidency would have passed directly to the Secretary of State—then John Hay—or another cabinet member, according to the Presidential Succession Act of 1886. But such a transition was neither clear nor tested, and it bypassed the democratic mandate the vice presidency implied.

This precarious arrangement continued until the ratification of the 25th Amendment in 1967, which finally established a procedure to fill a vice-presidential vacancy through presidential nomination and congressional confirmation. Before that, however, Americans lived with long stretches of vice-presidential vacancies—most famously during this very period between Hobart's death and the next inauguration.

As McKinley prepared for his 1900 reelection campaign, the need for a new running mate was not just strategic—it was essential. The nation could not afford another term without a clear second-in-command. And so, the Republican Party turned to a rising political star with a national reputation for courage, reform, and relentless energy.

The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt: From Reluctant Running Mate to Accidental President

Into the void left by Vice President Hobart’s death stepped one of the most energetic, enigmatic, and forceful personalities in American political history: Theodore Roosevelt.

At the time, Roosevelt was serving as the Governor of New York, where he had earned both acclaim and enmity for his vigorous reform agenda. A former Assistant Secretary of the Navy and celebrated leader of the Rough Riders during the Spanish-American War, Roosevelt had become a household name—a war hero whose charge up San Juan Hill was already mythologized in the press and public imagination. His brand of fearless leadership, paired with a moralistic devotion to reform, made him wildly popular with the public but deeply troubling to the entrenched Republican establishment.

Party bosses, particularly New York’s powerful political machine led by Senator Thomas Platt, found Roosevelt’s independence intolerable. He couldn’t be controlled, bribed, or bent to political favors. Platt, eager to remove the governor from state politics, seized an opportunity: elevate Roosevelt to the vice presidency, where—based on history—it was assumed he would be politically sidelined. The office was often considered a “political graveyard,” a position with little influence or power.

President McKinley, preparing for his 1900 re-election campaign, needed a running mate who could energize voters and bring youth, vitality, and war-hero credentials to the ticket. Roosevelt fit the bill. Though some party leaders hesitated, the public demand for “Teddy” was too strong to ignore.

Reluctantly, Roosevelt accepted the nomination. As he reportedly said, “I do not want to be Vice President. It is not a steppingstone to anything except oblivion.” But history would prove otherwise.

Roosevelt was inaugurated as Vice President on March 4, 1901—less than four months before fate would intervene.

The Document’s Significance to Collectors and Historians

This single-page document might seem simple at first glance, but it marks the beginning of a turning point in American history. More than just a formal statement of mourning, it set off a chain of events that would reshape the presidency, and the nation for generations to come.

The letter remains in fine condition, with gentle toning along the edges and McKinley’s bold signature anchoring the page. It is often accompanied by a rare ink signature of Garret A. Hobart himself—a haunting reminder of the man whose passing changed a nation.

Closing Thoughts: From Grief to Greatness

History does not always change with a bang. Sometimes it changes with a pen stroke on somber stationery. However in this case, it changed with both. This document is the embodiment of such a moment—a nation's sorrow giving way to a new chapter in its leadership.

From the quiet death of Vice President Hobart emerged one of America’s most robust and iconic leaders. Theodore Roosevelt’s legacy, etched into granite at Mount Rushmore and American memory alike, was shaped by this chain of events—and some would say it all began here, with McKinley’s solemn directive to honor a friend, a statesman, and a vice president.