The Crossroads of Justice: Ulysses S. Grant, the Ku Klux Klan Act, and a Rare Pardon from 1873

Share

In the annals of American history, few documents capture the tension between presidential authority, civil rights enforcement, and political reconciliation quite like a presidential pardon. When that pardon is signed by Ulysses S. Grant—the Union’s victorious Civil War general and 18th President of the United States—it becomes a window into a turbulent and transformative era.

In the annals of American history, few documents capture the tension between presidential authority, civil rights enforcement, and political reconciliation quite like a presidential pardon. When that pardon is signed by Ulysses S. Grant—the Union’s victorious Civil War general and 18th President of the United States—it becomes a window into a turbulent and transformative era.

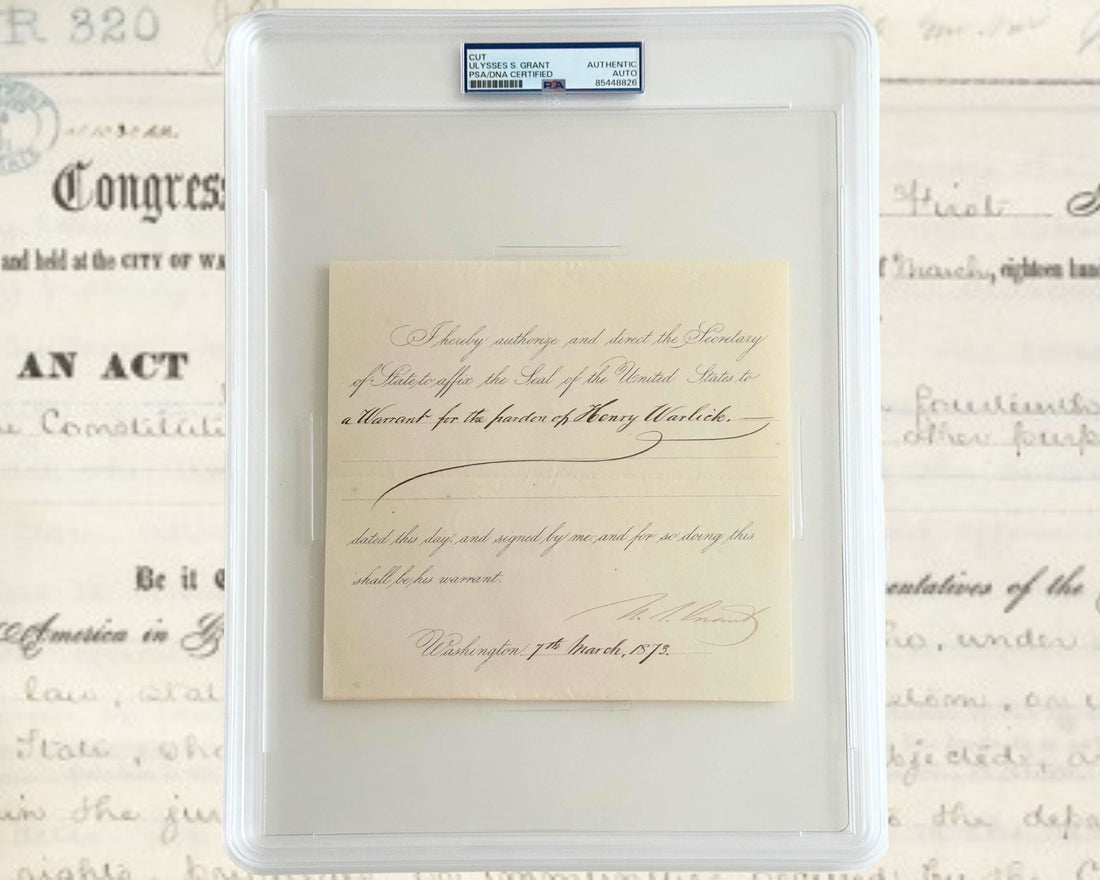

One such document, dated March 7, 1873, just three days after Grant began his second term as president, reveals a surprising and historically loaded act: a pardon for Henry Warlick, a South Carolinian convicted of Ku Klux Klan crimes. Though brief in wording, this pardon links directly to one of the most forceful campaigns the federal government ever undertook against white supremacist violence in the United States—the South Carolina Ku Klux Klan trials of the early 1870s.

The Pardon: A Rare & Controversial Presidential Order

The partially printed and manuscript-completed document reads:

“I hereby authorize and direct the Secretary of State to affix the Seal of the United States to a Warrant for the pardon of Henry Warlick, dated this day and signed by me; and for so doing this shall be his warrant.” — U.S. Grant, March 7, 1873

Grant’s signature—bold, fluid, and unmistakable—is affixed at the bottom right. The document itself is now preserved in a tamper-proof slab and certified by PSA/DNA as an authentic presidential autograph (certification number 85448826).

At first glance, it may appear to be a routine exercise of executive clemency. But the name “Henry Warlick” and the date of the pardon place this act in the middle of a national reckoning over Reconstruction, racial violence, and the limits of federal authority.

Who Was Henry Warlick?

While few personal records survive about Warlick himself, his name appeared in several newspaper reports of the time. On March 4, 1873, The Boston Globe reported:

“The President has pardoned Miles Carroll, Miles McCulloch, Henry Warlick and James A. Sanders of South Carolina, convicted of Ku-Klux crimes, and sentenced to confinement in the Albany penitentiary.”

Warlick had been convicted under federal law for his involvement with the Ku Klux Klan—specifically, crimes linked to organized racial terror in South Carolina during the Reconstruction era. His conviction and imprisonment were a direct result of President Grant’s aggressive crackdown on Klan activity, carried out through landmark legislation passed just two years earlier.

The Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871: Federal Power Versus Domestic Terrorism

To understand the pardon’s historical gravity, one must understand the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871, also known as the Third Enforcement Act. This legislation was a response to widespread violence across the South, especially in places like South Carolina, where the Klan used intimidation, assault, and murder to suppress Black political power and restore white dominance.

Signed into law by President Grant in April 1871, the Act gave the federal government sweeping powers to combat racial violence:

Authorized the President to suspend habeas corpus in areas where Klan violence rendered local law enforcement ineffective.

Allowed federal troops to intervene in states that failed to protect their citizens.

Permitted federal prosecution of individuals engaged in conspiracies to deny civil rights.

The act was a direct and unprecedented use of federal power to protect Black citizens and Republican political leadership in the postwar South. Grant used these powers decisively, declaring martial law in nine South Carolina counties and launching a wide-scale effort to root out Klan activity.

The South Carolina Klan Trials (1871–1872): A Federal Show of Force

The South Carolina Klan trials were the most extensive legal action ever taken against domestic white supremacist terrorism in the 19th century. Beginning in late 1871, over 600 individuals were indicted, with many tried and convicted in Columbia and Charleston. The Justice Department, led by Attorney General Amos Akerman and later Solicitor General Benjamin Bristow, relied on the testimonies of Black citizens and former Klansmen who turned state’s witness.

One of the most notorious sites of Klan violence was York County, where armed Klan groups terrorized freedmen, teachers, and Republican officials. The federal response was swift and powerful—hundreds of arrests, successful prosecutions, and long prison sentences at places like Albany Penitentiary in New York, where Warlick was confined.

These trials were widely publicized and initially praised by civil rights advocates. But as the 1870s wore on, public support for Reconstruction began to erode, and the political appetite for continued federal intervention waned.

The Timing of the Pardon: March 1873

Grant’s pardon of Warlick—alongside three others convicted in the trials—came at a symbolic moment: just three days after his second inauguration. The early days of Grant’s second term were marked by a political shift toward reconciliation, and by growing pressure, particularly from Democrats and moderate Republicans, to soften the federal government’s stance toward the South.

It is unclear whether the pardons were politically motivated, a gesture of leniency for minor offenders, or the result of lobbying by local interests. But they represent a sharp contrast to the aggressive prosecution policy that characterized Grant’s first term.

A Link to America’s Reckoning with White Supremacy

Today, the Warlick pardon stands as a powerful and rare artifact of this fraught chapter in American history. It embodies the contradictions of Reconstruction: a moment when the federal government, under Grant’s leadership, boldly attempted to dismantle racial terrorism—only to have those efforts later diluted by political compromise and public fatigue.

Grant’s signature on this document is a testament to a president who used the power of his office—first to pursue justice with unprecedented force, and later to balance that force with clemency, rightly or wrongly.

For collectors of presidential documents, Civil War history, and civil rights milestones, this pardon is a compelling artifact that speaks volumes about the promise and peril of American Reconstruction.While most presidential pardons fade into bureaucratic obscurity, this one survives as a vivid reminder of a nation at a crossroads—still wrestling with its deepest wounds and contradictions. That it bears the unmistakable hand of Ulysses S. Grant only adds to its historic weight. Whether viewed as an artifact of justice, reconciliation, or moral complexity, this 1873 pardon is a rare, authentic piece of the American story.

This incredible piece of American History is available for purchase in our gallery!

If you are interested in selling your piece of Civil Rights or U.S. Grant history, simply click below: