Forged in the Lab, Carried in the Sky: Rare Relics from the Manhattan Project and the Enola Gay

Share

History often hides in plain sight, in the tools and objects once used by ordinary people carrying out extraordinary tasks. At Historical Autographs Gallery, we are privileged to present two singular relics that together frame the story of the atomic age:

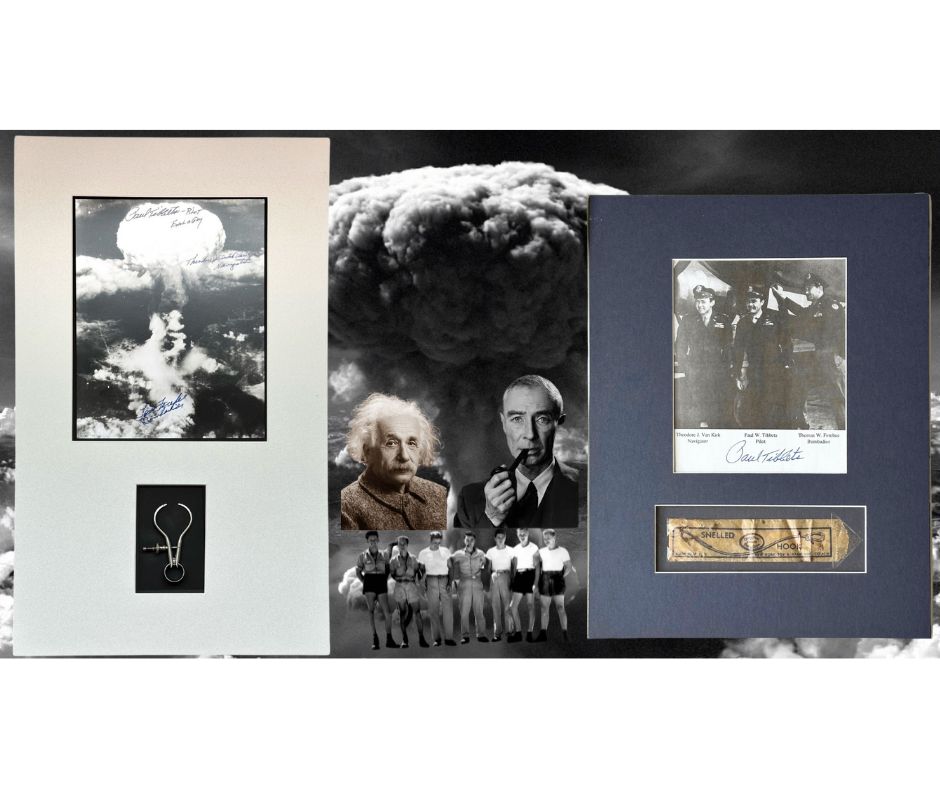

A caliper divider tool used in the construction of the first atomic bombs at Los Alamos, once belonging to foreman Gus Schultz.

A survival kit fishing hook carried aboard the Enola Gay by tail gunner George R. Caron during the Hiroshima mission.

Individually, they represent two very different worlds, the workshop of Los Alamos, and the combat flight deck of a B-29 bomber. Together, they tell the arc of one of the most consequential events in modern history.

The Manhattan Project: From Einstein’s Warning to Oppenheimer’s Laboratory

The story begins in 1939, when Albert Einstein and physicist Leó Szilárd co-signed a famous letter to President Franklin Roosevelt warning that Nazi Germany might be developing a nuclear weapon. This letter spurred the creation of what became known as the Manhattan Project — the most secretive and ambitious scientific endeavor ever attempted.

By 1942, under the leadership of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the government established Project Y at Los Alamos, New Mexico, where some of the greatest scientific minds of the century — Niels Bohr, Enrico Fermi, Richard Feynman, and others — converged. But theory alone could not produce a bomb. The designs for uranium “Little Boy” and plutonium “Fat Man” required meticulous engineering and fabrication, where even a fraction of a millimeter could mean the difference between detonation and dud.

Gus Schultz and the Caliper Divider Tool

This is where men like Gus Schultz, foreman of the Los Alamos machine shop, played a decisive role. Schultz oversaw the teams who turned physicists’ equations into reality, fabricating implosion triggers, bomb casings, and containment chambers. His shop was praised by Oppenheimer himself, who wrote to Schultz:

“The laboratory has leaned very heavily on you, and there have been times when your shops have stood between us and failure—many such times... none of us is so foolish as to think we could have done it without you.”

The caliper divider tool once used in Schultz’s shop, now mounted beneath a signed photo of the Hiroshima mushroom cloud, is a rare surviving instrument of this effort. Simple yet essential, the tool ensured precision in the machining of bomb components. It is paired with signatures from the three Enola Gay crewmen who ultimately delivered the weapon Schultz helped build: Paul Tibbets (Pilot), Tom Ferebee (Bombardier), and Theodore “Dutch” Van Kirk (Navigator).

In a field where Trinitite, the green glass created by the Trinity Test is often the most accessible relic, an actual workshop tool from Los Alamos stands virtually alone in the marketplace. It is not a symbol, but a tangible link to the making of the atomic bomb.

From Theory to Flight: Preparing the Enola Gay

By the summer of 1945, with the successful Trinity Test proving the weapon’s power, the United States prepared to end the war with Japan by using the new bomb. The Enola Gay, a specially modified B-29 Superfortress, was chosen for the mission.

But success was not guaranteed. The crew faced extraordinary risks:

Enemy defenses: Though Japan’s air defense network was weakened, there remained the possibility of fighters or anti-aircraft fire.

The bomb itself: Never before had “Little Boy” been dropped in combat. No one could be certain it would function properly, or what effects it might have on the crew.

Mission endurance: The flight from Tinian Island to Hiroshima was six hours one way, leaving the men isolated over vast stretches of Pacific Ocean. If the plane was forced to ditch, survival gear could be the difference between life and death.

George Caron and the Survival Kit Fishing Hook

Seated at the very rear of the Enola Gay was George R. Caron, the plane’s tail gunner and only defensive weapon against enemy fighters. Strapped to his body was the Type C-1 Emergency Survival Vest, containing a small fishing kit, snares, and cloth maps — just enough to give a downed airman a fighting chance in open seas.

Among the items carried by Caron was a simple fishing hook, preserved to this day in its original wartime packaging. It is a relic of preparation, of the personal risks faced by each crew member who undertook this mission. When the bomb detonated at 8:15 a.m. Hiroshima time, Caron, camera in hand, was the first of the crew to see and photograph the towering mushroom cloud that followed.

This hook, along with others from Caron’s kit, comes with impeccable provenance: a notarized Autograph Letter Signed by Caron, dated May 27, 1989, in which he certifies that the survival kit was indeed carried aboard the Enola Gay on the day of the Hiroshima bombing.

Notably, Caron’s AAF cloth survival chart, also from his vest, sold at Heritage Auctions in 2022 for $68,750, underscoring the immense historical and collector value of these personal artifacts.

Two Relics, One Legacy

Seen together, but offered separately, these two artifacts: the caliper divider from Los Alamos and the fishing hook flown on the Enola Gay, trace the story of the atomic bomb from scientific conception to combat execution:

The caliper speaks of the painstaking precision of the machinists and engineers who gave form to Oppenheimer’s designs.

The fishing hook speaks of the human risks borne by the airmen who carried those designs across the Pacific and into history.

Between them lies the story of the Manhattan Project, the Trinity Test, the mission to Hiroshima, and the dawn of the nuclear age.

How do we prove it?

Provenance is the lifeblood of historical artifacts, and both of these pieces come with impeccable documentation. The caliper divider tool comes from the estate of Gus Schultz, foreman of the Los Alamos machine shop, and is supported by copies of J. Robert Oppenheimer’s personal letters praising Schultz’s indispensable work, Schultz’s Los Alamos ID card, and even his wife’s wartime diary reflections. The fishing hook from the Enola Gay survival kit is authenticated by a notarized Autograph Letter Signed by tail gunner George R. Caron; we hold the original letter in our collection and provide certified copies to buyers of the hook. In this document, Caron certifies that the Emergency Sustenance Vest Type C-1 and its contents were carried by him aboard the Enola Gay during the Hiroshima mission. Together, these documents provide an unbroken chain of custody, leaving no doubt that these relics are genuine survivors of the Manhattan Project and the first atomic bombing mission. At Historical Autographs Gallery, we are meticulous about provenance, if the slightest detail does not fully align, we simply will not offer the piece.

Closing Reflections

Objects like these remind us that history is not abstract. It was built by hands, everyday machinists tightening bolts in Los Alamos, gunners strapping on survival vests in Tinian and carried into reality by decisions that reshaped the 20th century.

For collectors and institutions, these artifacts represent more than memorabilia. They are direct, physical links to the moment when science, war, and morality collided on a scale never before seen.

These are the very types of relics preserved in world-class museums, yet now, through our gallery, they can be part of your personal collection at home.

We are always seeking historically significant artifacts — if you own any Manhattan Project, Enola Gay, or World War II relics and are interested in selling, please don’t hesitate to reach out to us.